Python and Java are both object-oriented languages but their syntax differs greatly. In this section, we explore the syntax and program structure of Python needed to construct the most basic programs.

Before we begin, let’s look at the classic “Hello World” program written in Java

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main( String[] args ) {

System.out.println( "Hello World" );

}

}

and the equivalent in Python

print "Hello World"

From this example, one obvious difference between the two languages is the wordiness of Java. You will come to see that Python provides built-in operators and shortcuts for many of the common operations performed in computer programs.

Statements

The Python syntax, as with all languages, is very specific when it comes to statement structure. Being familiar with Java, the structure of a Python program may take some getting used to. On the other hand, if you have experience using a scripting language such as Perl or Ruby, the structure will be more familiar.

Line Format

Statements in Python do not end with a semicolon as they do in Java. Instead, the end of a statment is indicated by the normal line termination (new line or carriage return)

print "How are you today?"

Since statements are terminated with a semicolon in Java, a single statement can span multiple lines

System.out.print

(

"Hello World!!"

)

;

Since the end of line indicates the end of a statement, the Python interpreter expects a statement to stay on a single line. If a statment is too long to fit on a single line, however, you can use a backslash (\) at the end of the line and continue the statement onto the next line.

- (originalValue * 2)

name = "John "\

"Smith"

For function calls and method invocations which use a pair of parentheses, Python will automatically search for the closing parenthesis and thus backslashes are not needed to indicate line continuation.

"name",

avg )

| Note:

String literals can not be broken across lines without the use of the backslash. |

Comments

A comment in Python, like most scripting languages, begins with a hash (#) symbol and continues until the end of the line.

result = 0 # so is this

Statement Blocks

Python uses the indentation level of statements to define statement blocks instead of begin/end delimiters or braces ({})

total = total + i

i = i + 1

print "The total = ", total

In Java, this code segment would be written as

while( i <= 20 )

{

total = total + i;

i = i + 1;

}

print "The total = " + total;

| Note:

Good programmers typically use indentation to specify statements within a given block no matter which language they are using. In Python, the indentation is required. |

Python statements which require a statement block include a colon (:) as part of their syntax. In this example, the condition of the while statement includes a colon which flags a required statement block.

Only statements within a block or the parts of a statement continued from a previous line may be indented. The top-level statements of the program, which are at file level, must have no indentation. A few important notes related to statement blocks:

- The number of spaces used to indent the statements within a block does not matter. What matters is that all statements within the block must have the same indentation level.

- The first statement with a different indentation level flags the end of the block. When using interactive mode, a blank line will also flag the end of a statement block.

| Warning:

All statements within a given block must be indented with either blank spaces or tab characters, but not a mixture of the two. |

Identifiers

Identifiers in Python are case senstive and may be of any length. The rules for constructing an indentifier are very similar to those of Java. The only difference is that the underscore is the only special character that can be used; a dollar sign is not allowed. Thus, Python identifiers

- may only contain letters, digits, or the underscore, and

- may not begin with a digit.

You can not use a reserved word as a user-defined identifier. The following is a list of reserved words in Python

and assert break class continue def del elif else except exec finally for from global if import in is lambda not or pass print raise return try while

There is also a group of identifiers used to name built-in functions and standard classes. You should avoid using these for user-defined identifiers

float int string

Primitive Types

Python is entirely object-based which means all data values in Python are represented as objects and are defined by classes including the simple primitive types.

Numeric

Python has four primitive numeric classes including

- integer

- similar to an

intin Java but the size of a Python integer is platform dependent. Though, a Python integer does consist of at least 32-bits. Octal and hexadecimal literals can also be specified as in Java.

-9 50 0x4F 077

- long integer

- represented in software and provide unlimited precision. There is no equivalent type in Java. The use of this numeric type should be limited since it is implemented in software and requires extra computations. A long integer literal is indicated by following the value with a capital

L

456L 4567812391234L

- floating-point

- similar to a

doublein Java but the size is platform dependent. - complex

- used to represent complex numbers which contain real and imaginary parts. There is no equivalent type in Java. The two components of a complex value are each stored as a float.

3 + 4j 4.25 - 0.01j

Boolean

While Python does not have classes to represent single characters or unsigned integers, it does have a primitive boolean class and defines the two constants True and False

error = False continue = True

Strings

Python strings are an immutable ordered sequence of characters whose value can not change once created. String literals are represented using a pair of either single (‘) or double (“) quotes to enclose the character sequence.

'string' "another string" "c"

Python also allows for the creation of block strings using tripple quotes, details for which are provided in a later chapter. Characters in Python are represented as a string containing a single character.

Sequences

Python has two additional primitive sequence classes including

- list (or array)

- an ordered sequence of objects of any type. A literal list is specified using square brackets.

[ 0, 1, 2, 3 ] [ 'abc', 1, 4.5 ] []

- tuple

- similar to a list type but a tuple can not be changed once it has been created. A tuple literal is specified using a comma separated list and may be enclosed within parentheses.

1, 2, 3 ( 1, 4, 5.6, 'a' ) (5,)

Collections

Python provides two primitive collection types

- dictionary (or hash)

- provides a hashing structure in which each item contains a key and a value. A dictionary literal is represented by enclosing one or more key/value pairs within braces.

{ 123 : "bob", 456 : "sally" }

- set

- an unordered collection of immutable values which provide typical mathematical set operations. Python does not provide a mechanism for specifying literal sets. Instead, the various class methods are used for creating and manipulating set objects.

Variables

As previously indicated, all data types in Python are treated as classes including the primitive types. Thus, all variables in Python store references to objects. In Java, primitives are automatically created and stored directly in memory while objects are dynamically created and stored as references.

Declarations

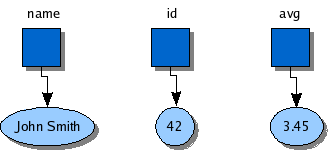

In Python, variables are not specifically created using a variable declaration. Instead, they are created automatically when they are assigned an object reference. The following code segment creates three variables

idNum = 42

avg = 3.45

which would be equivalent to the following in Java

String name = "John Smith";

int idNum = 42;

double avg = 3.45;

A variable itself does not have a type and thus can store a reference to any type of object. It is the object, which has a data type. The following diagram illustrates the creation of the three variables from the example above.

Literal values are actually nameless objects of their respective type. Thus, a literal value of 42 is actually an integer object which has the value 42. Each unique literal value within a program results in a unique object.

| Note:

As in Java, a variable can not be used before it has been assigned a reference to some object. Attempting to do so will generate an error. |

Assignments

Python uses a single equal sign (=) for assigning an object reference to a variable. When an assignment statement is used, the reference of the object on the right-hand side is copied and stored in the variable on the left hand side, not the data.

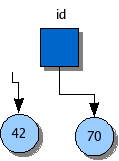

When a new reference is assigned to an existing variable, the old reference is replaced. Consider the following code segment

which alters the idNum variable reference

An existing variable can be assigned a reference of any type. Thus, no type checking is performed when an assignment operation is performed. In the following code segment, the idNum variable is assigned a string instead of an integer

In diagram form, the change would appear as follows

When one variable is assigned to another

the result is an alias as in Java since both variables refer to the same object.

When all references to an object are removed, the object is automatically destroyed as is done in Java.

Constants

Consider the following Java code segment which creates two constant variables

final double TAX_RATE = 0.06;

final int MAX_SIZE = 100;

Python does not support constant variables. Instead, it is common practice for the programmer to specify constant variables as those named with all capital letters. To create the two constant variables, you should write

MAX_SIZE = 100

It is important to note, however, there is no way to enforce the concept of a constant variable and keep its value from being changed. By following the standard convention, however, you provide information to yourself and others that you intend for a variable in all caps to be constant throughout the program.

Mathematical Operators

Python supports the common mathematical operations for both integer and floating-point values as found in Java

| Operator | Description |

% | Modulus |

/ | Division |

* | Multiplication |

+ | Addition |

- | Subtraction |

and two operators not available in Java

| Operator | Description |

** | Exponentiation |

// | Division (floored) |

The statement x ** y computes the exponentation xy while x // y computes the mathematical floor of x / y in which the fractional part is truncated. Both of these operators can be used with integer or real values.

The operators have the expected order of precedence as found in mathematics and parentheses can be used to override that order. Python also supports the augmented assignment operators

+= -= *= /= %= **= //=

but it does not have the increment (++) and decrement (--) operators.

Division and Remainder

Python supports both integer and real division. The / operator works the same as in Java; if both operands are integers, integer division is performed, otherwise the result is real division. The remainder of integer division is computed using the % operator. Python adds the // operator which always performs integer division, no matter what type of operands are used. Thus

Mixed Types

If the two operands are of the same type (i.e. float), the type of the resulting value will be the same; if they are different, the operand of lesser rank will be converted to the higher rank. The conversion is only temporary for use in the evaluation of the given operator; the actual object is not modified. In Python, the ranks of the numeric types are

int > long > float > complex

Type Conversions

Python will implicitly convert between the numeric types as needed. All other conversions, however, must be explicit. Python provides a number of built-in functions to handle these conversions. Descriptions and examples will be provided in the following chapters.

Main Routine

Every program must have a unique starting point; a first statement to be executed. In Java, the starting point is the first statement within the main() routine. Consider the following Java program

// Compute the sum of the first 100 integer values and print

// the results.

public class Summation {

public static void main( String[] args ) {

final int NUM_VALUES = 100;

int summation = 0;

int i = 0;

while( i <= NUM_VALUES ) {

summation = summation + 1;

i = i + 1;

}

System.out.println( "The sum of the first " + NUM_VALUES

+ " integers is " + summation );

}

}

In Python, the first statement to be executed, is the first statement at file level (outside of all functions and class definitions). The Summation.java program would be written in Python as follows

# Compute the sum of the first 100 integer values and print

# the results.

# Initialize a constant variable.

NUM_VALUES = 100

# Compute the sum.

summation = 0

i = 1

while i <= NUM_VALUES:

summation = summation + i

i = i + 1

# Print the results.

print "The sum of the first", NUM_VALUES, \

"integers is", summation